Short Summary

The city has a parking monopoly. It owns 7 parking structures and 8 surface lots and forbids private facilities from competing with the city. The parking structures are not self supporting and require large taxpayer subsidies.

In effect, the city uses taxpayer money to make parking and driving artificially cheap. This worsens traffic congestion, harms the environment, and burdens the city’s finances. It also contradicts the purpose of the parking system.

Ending the monopoly would reduce traffic, free up space downtown, and make it easier for residents to get monthly parking permits. It would also save the city huge amounts of money.

Contents

- 1 Short Summary

- 2 Long Summary

- 3 The Monopoly

- 4 Financial Gains From Ending Monopoly

- 5 Other Reasons to End The Monopoly

- 6 Managing the Transition

Long Summary

The parking system works like this:

The city borrows money to build new parking structures. It then charges less for parking than what is necessary to pay its debts. This forces the city to use property tax revenue to pay debts. After a few decades, the city completes its debt payments, and the structures make small profits.

These parking investments are bad for the city’s finances, even though new structures eventually make a profit. This is because the city could make better investments with the same money.

According to the DDA‘s deputy director, total estimated bond payments for the Library Lane project equal $72 million. This figure is also shown on the DDA’s 2013 outstanding debt statement.

The structure has an annual income of about $1 million including the city’s 17% cut of revenue. At this rate, the structure will only generate $23 million in before-debt income from 2013-2035.

$23 million in income – $72 million in debt = – $49 million, or -$2.1 million a year from 2013-2035.

It might not seem bad for the structures to lose money for decades, so long as they eventually make money. But in fact, the structures never make a profit after accounting for opportunity costs. When the city invests in a parking structure, it loses the money that could have been gained from investing in a profitable investment, like road maintenance.

For example, instead of building the underground structure, the city could have used $2.1 million a year to increase its annual road repair budget by roughly 20%. This would have allowed the city to do more preventative maintenance, which can reduce the costs of repairs by 25% compared to neglecting roads and then reconstructing them.

Other new structures are not so extremely unprofitable, but they are still bad investments. For example, the city will have to pay $11.2 million between 2013-2032 for the First and Washington structure, or $0.6 million a year. Annual income is also about $0.6 million. At this rate, the structure will not make money in its first 20 years.

For both of these structures, the city’s losses are larger for other reasons that are not shown in the data:

- Structures often need repairs. Repair costs are not included in the operating income statement, but they are expensive.

- The city’s gives up the property tax revenue that privately owned structures would generate. Since these structures are large buildings in the downtown, the loss is substantial.

Aside from the financial costs, the parking monopoly is bad for a number of other reasons:

- Subsidized parking worsens traffic and air pollution by encouraging people to drive.

- Parking lots take up valuable downtown space that could be used for other purposes.

- The artificially low cost of monthly permits causes waitlists.

- The ban on private facilities stops businesses from competing to offer parking in better locations.

For these reasons, the city should legalize private parking facilities and sell its own facilities. As a first step, it should sell six of its surface lots. I estimate that selling these lots would generate roughly $33.0 million that could be used to improve city services in the short run. In the long term, the new tax revenue from selling the lots would probably be much larger than the loss in parking revenue.

Note: If there is public support for turning one of the surface lots into a downtown park, I would support the proposal.

Eventually, the city should also sell its parking structures. It should set a minimum asking price, so that selling them is guaranteed to benefit the city’s finances.

The Monopoly

The city owns 15 parking facilities.

The city owns 7 parking structures and 8 surface lots. It often builds new structures, including an underground structure in 2009 that cost roughly $50 million, and a structure in 2013 that cost about $10 million. It pays for new structures with bonds. For example, the two new structures have outstanding debt worth $83 million.

A city agency, The Downtown Development Authority, operates and maintains these facilities and about 2200 on-street parking meters. It also leases two private lots owned by the First Martin Corp. The DDA contracts with Republic Parking, a private company, to manage the system.

The city bans private parking facilities.

The city’s zoning rules ban private parking facilities. In the R4C zones that surround downtown, parking structures and lots are not a permitted use. In the downtown districts, they are only allowed as a special exception.

To get special exemptions, property owners have to get approval from the planning commission. The commission is supposed to only grant exceptions that jibe with the city’s master plan. The downtown master plan has listed under “Parking Principles,” “Seek to accommodate all Downtown parking activity within the DDA parking system.” If a property owner asks for an exemption to run a parking facility, the request will probably fail, because exemptions contradict the master plan.

Financial Gains From Ending Monopoly

The city should amend its zoning code to allow private parking facilities in the downtown, and then sell city surface lots. The city has already sold the Y lot, and intends to sell part of the library lane lot. Selling other facilities will provide funding for road repairs, pedestrian infrastructure, and other needs.

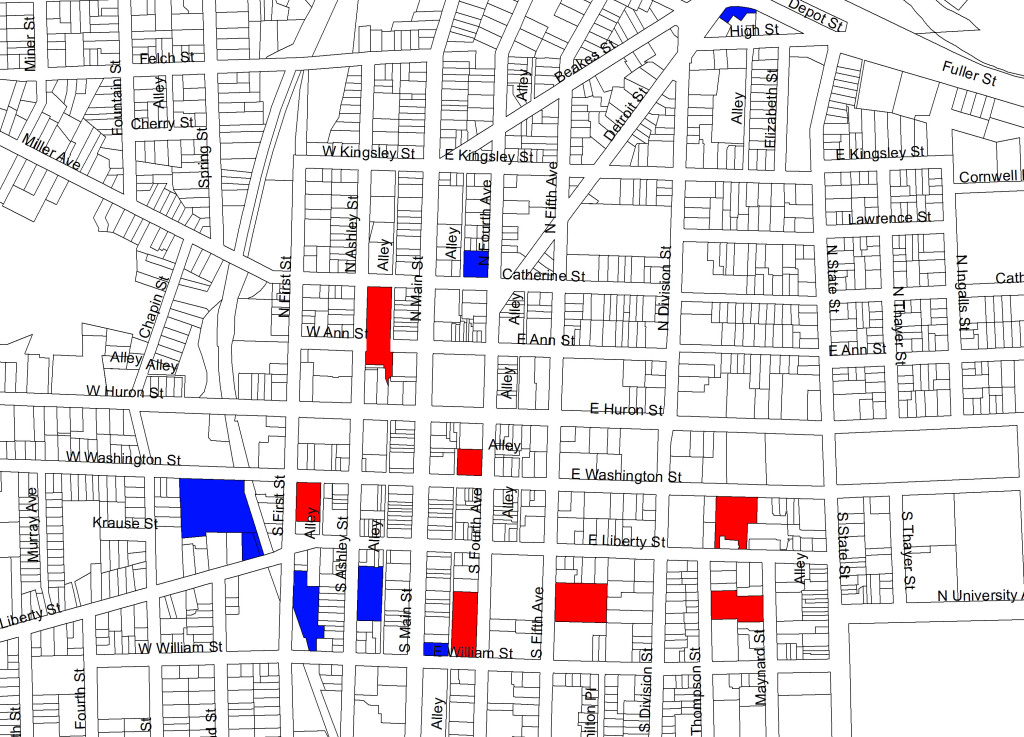

The 2011 DDA parking agreement lists 6 structures and 9 lots that are fully owned by the city. Since then, the city sold the Y lot, and built the structure below City Apartments at First and Washington That means there are 8 lots and 7 structures left. If we only count lots used for primarily for public parking, we eliminate the the farmers’ market space, and the lot for city hall. That leaves 6 surface lots (blue) and 7 structures (red). If the city sells its facilities, it will lose parking revenue, but the gains will more than make up for the losses.

Surface Lots

In the short term, selling six lots would generate roughly $33 million.

The value of each surface lot depends on its size, location, zoning, and other factors. Below, I estimate the value of each surface lot by comparing existing lots to past lots that have already been sold. The only variable I adjust for is size. This is a crude way to estimate value, but it gives a general sense of how much the lots are worth.

Two lots have recently been sold. The 24,437 sq ft. City Apartments Lot was sold in 2011 for $3.2 million at $131 per sq ft. The 35,089 sq ft. Y Lot was sold in 2014 for$ 5.3 million at $151 per sq ft. For the estimates below, I assume that the lots are worth $140 per sq ft.

- 415 W. Washington 109,842 sq ft.

- Estimated worth at $140 per square ft : $15.7 million

- 2013 operating income + city payment: $148,517

- Return on Asset: 0.9%

- Broadway Bridge 8,414 sq ft.

- Estimated worth at $140 per square ft : $1.2 million

- 2013 operating income + city payment: N/A

- Return on Asset: N/A

- First and William 38,884 sq ft.

- Estimated worth at $140 per square ft : $5.4 million

- 2013 operating income + city payment: $107,252

- Return on Asset: 2%

- Fourth and Catherine 16,700 sq ft.

- Estimated worth at $140 per square ft : $2.3 million

- 2013 operating income + city payment: N/A

- Return on Asset: N/A%

- Palio Lot (William and Main) 8,220 sq ft.

- Estimated worth at $140 per square ft : $1.2 million

- 2013 operating income + city payment: N/A

- Return on Asset: N/A

- South Ashley 54,540 sq ft.

- Estimated worth at $140 per square ft : $7.6 million

- 2013 operating income + city payment: $372,453.

- Return on Asset 5%

Total area: 236,000 sq ft.

Total worth at $140 per sq ft: $33.0 million

In the long term, new tax revenue would more than compensate for the loss of parking income.

Selling the lots would give the city’s finances a temporary boost in revenue, but it would also benefit the city’s finances in the long term, because the buyers of the parking lots would probably construct buildings in their place. Those buildings would be a long term source of tax revenue that would likely outweigh the parking revenue losses.

Income from surface lots is around $0.7 million a year.

For some of the lots, operating income data is available, which I show above. This data can be used to estimate the income from the other lots.

Average income (operating income + city payment) per sq ft: $3.1

Since the total area of all the lots is 236,000 sq ft, I estimate that parking income would be $0.7 million (236,000 sq ft x $3.1).

Future tax revenue would be something like $1.5 million a year.

For example, the City Apartments building that went over a former city lot has a taxable value of $9.2 million. The city’s millage rate is 16.5. That means a new building with the value of City Apartments would generate about $152,000 a year for the city and more for other governments like the Ann Arbor Public Schools. The DDA’s cut of taxes from new buildings is maxed out, so new revenue would go directly to the city’s treasury.

City Apartments replaced a parking lot that was 24,437 sq ft. That means the city gained about $6.2 in tax revenue per sq ft. If new buildings over the 6 surface lots generated the same amount of tax revenue per sq ft, they would yield about $1.5 million a year for the city. That means, all together, the city would earn a net-gain of $0.8 million a year by selling its surface lots ($1.5 million in profits – $0.7 million in losses).

Structures

It is harder to estimate the value of the 7 parking structures because none of them have been sold recently. However, the city should still sell them if the asking price is high enough. It doesn’t make sense to forgo revenue in order to subsidize parking.

The structures are probably worth more to a private owner than to the city.

The city could sell its structures at a profit if buyers are willing to pay more than the structure’s worth to the city. There are probably buyers willing to do this, because they could either raise parking rates, or convert structures to apartments, offices, or retail. Conversions would make parking more expensive, and housing, retail, and office space cheaper. This would be good, because cheaper parking causes traffic congestion and pollution, whereas cheaper residential and commercial space does not cause these harms.

The city should sell its structures with a minimum asking price.

To sell the structures at a profit, it is first necessary to determine their value to the city. This requires several pieces of information for each structure:

- Annual revenue.

- Annual expenses, including capital expenses for maintenance.

- The return rate on the city’s best available investment.

Once these are known, we can determine each structure’s annual profits. Then, we can consider how much this stream of profit is worth today. To do this, we determine how much money it would take to get an equivalent stream from the city’s best alternative investment.

For example, suppose a structure has an annual income of $0.5 million. Perhaps the city’s best available investment gets a 5% annual return. In that case, the structure would be worth $10 million, because a 5% return on $10 million is $0.5 million.

If elected, I will ask city staff to provide the necessary information to make this kind of estimate. With accurate information, the city can sell its structures with a minimum asking price. This will ensure that any sale is a net-gain for the city.

Other Reasons to End The Monopoly

Problems with the Monopoly

The justifications for a monopoly are vague and contradictory.

The city’s master plan does not directly state why it operates a monopoly. However, it lists a guiding “first principle” for parking and transportation:

Parking is one part of a multi-modal transportation plan approach to providing Downtown access and mobility.

Parking allows people to access locations by car. This does not explain why the city needs to provide it. Bread is one part of a multi-modal plan of survival, but the city does not run bakeries. Maybe parking is uniquely beneficial and worthy of government subsidy. But then why does the zoning code ban private facilities? Another principle of the parking system suggests an answer:

Support modes of access that promote efficient land use patterns, environmental sensitivity, non-motorized mobility options, and the community’s overall quality of life.

The DDA’s Public Parking and Transportation Demand Management Strategies Plan expands on this idea:

Successful downtowns have long relied on an understanding that parking demand can be “managed” by making some transportation and parking choices faster, more convenient, easier, or cheaper.

This statement references the urban planning literature that argues for parking taxes and restrictions. Donald Shoup, who is cited in the DDA report, argues that mandatory free parking is a subsidy for driving and pollution. It increase traffic, and harms the poor by compelling people to build cities that are only accessible by car. His book is called the High Cost of Free Parking. A Vox interview provides a good summary of his ideas.

Shoup’s argument can be extended to subsidized spaces. If people do not have to pay the full cost of their parking, they will drive more. The DDA builds off this argument in its “best practice guidelines:”

- “Tax parking spaces. Reform existing tax policies that favor free parking.”

- “Avoid excessive parking supply. Apply reduced and more flexible parking standards that reduce requirements if parking is efficiently managed.”

Given these “best practices”, it seems that the DDA wants to reduce the amount of parking available. But a different section of the DDA’s plan seems to reject this:

While some view public parking as being in conflict with sustainable transportation, the reality remains that parking is an interconnected part of the larger transportation system, and every day people are making complex choices for themselves based on the options available to them at the time they need them.

If public parking is consistent with sustainable transportation, then why is it illegal for companies to sell parking to the public? Perhaps the DDA wants there to be some parking available, but not as much as there would be with an open market. This is a reasonable goal, but using taxpayer money to make parking artificially abundant does the exact opposite.

The monopoly discriminates against residents.

In 2007, city council has approved a set of parking recommendations. They include two different plans for setting parking rates: an “augmented market approach” and a “market approach.” Both approaches include “toolbox strategies” to manage demand without raising prices.

These strategies are designed to reserve parking spots for favored groups. The recommendations warn that without these tactics, “the business community” might be priced out by residents. One toolbox strategy is to charge hourly rates to favor commuters over residents.

A debit account system that charges all parking based on hourly rates would make monthly parking costs much higher for residents compared to commuters. Charging all customers for each hour of use will roughly triple the monthly cost of residential versus commuter parking. This greatly favors employees over students, though it would also likely encourage more on-site parking provision at new residential developments.

It seems unfair for a public utility to deliberately forgo revenue to favor certain kinds of people over others. A counter argument is that the city should help poor or middle class “business community” victims at the expense of wealthy residents. I see two problems with this argument.

- Not everyone in the business community is poor or middle class. Giving them artificially cheap parking is inefficient and unfair.

- There are other more effective ways to help the poor. The city could instead offer annual low-income AATA passes, increase housing subsidies, or do something else to make sure that aid goes to the people who need it.

Benefits of Ending the Monopoly

Fewer parking spaces will reduce traffic.

There is a close relationship between the amount of parking in a city and the amount of traffic, because all vehicle trips need to start and end in parking spaces. When the city creates parking spaces that would not exist in an open market, it increases traffic congestion. That is what the city is doing now. This is the exact opposite of what the parking system’s goals are, which is to “manage” demand by making parking more expensive.

Legalizing private facilities will make parking more convenient and dependable.

While the monopoly probably makes parking cheaper, it also makes it less reliable and convenient. If the city sets the price of parking too low, or fails to make spaces available for some other reason, there is little recourse for people who need reliable parking options. The Ann Arbor News reported in 2013 that hundreds of people are on waitlists for monthly parking permits. If private facilities were allowed, anyone could get a permit for the market price.

With or without a fee, private options will help people who need reliable parking. The city’s current parking recommendations agree that reliability is more important than price for many people:

The Project Team is convinced, following focus group meeting with business leaders and real estate brokers, that the lack of predictable parking access is currently a greater deterrent to employers than parking costs.

With private facilities, drivers would gain the reliability of having many different options in case one service does not meet their needs.

Managing the Transition

Selling facilities will cause disruptions that the city will have to address. Some developers have leases that fulfill their off-street parking requirements. Instead of providing free parking on-site, Developers can make a payment in lieu of required parking by leasing spaces for 15 years, or by paying a $55,000 per space fee. This program will not be possible if the city no longer owns structures.

The city could replace the payment in lieu program with a developer mitigation fee. The fee would require developers to pay for new buildings’ effects on traffic, road wear, and parking availability, rather than require developers to lease parking spaces. Fees like this are legally defensible when they are carefully constructed. The city can move existing leases agreements into other structures, or substitute them for cash payment plans. If that fails, it can waive the agreements.

The sales will also affect short term permits. The city should make agreements with the investors who buy facilities to accommodate existing customers with monthly permits. Eventually, private parking facilities will benefit the hundreds of people on permit waiting lists.

When selling structures, the city should retain significant public alleys and walkways adjoining them, such as the graffiti alley on Liberty.